|

Like many physics professors, David Meltzer thought he was a good

teacher. He was dedicated to helping students, and he believed he gave

very good lectures. Yet he couldn’t help but notice that despite his

efforts, his students just weren’t learning what he wanted them to

learn .

David Meltzer at the blackboard.

|

Rather than just continuing to lecture in the same old way, Meltzer

sought to find out why his students had so much trouble. “I began to

read studies, and I found my experience was common and there were

reasons for it, and there were ways one could address the problem,” he

says. So Meltzer familiarized himself with the latest research in

physics education, and he developed a new way of teaching.

Now, in professor Meltzer’s physics classes at Iowa State University ,

students don’t just sit back and listen, they are actively engaged in

thinking, answering questions, and discussing tough concepts with their

fellow students.

Instead of a

traditional lecture where the professor talks for an hour and then asks

if there are any questions, Meltzer often gives a short overview or

introduction to a topic, then poses a series of multiple choice

questions, which students answer by holding up a flashcard with a

letter. The students usually have a few minutes to think over their

answers and discuss with fellow students before holding up their

flashcards. If the class is split, Meltzer will encourage a debate, and

then try to guide the students to the correct answer. This technique,

which Meltzer uses even in large lecture classes, not only keeps the

students actively engaged, it lets the lecturer know whether the

students are grasping the concepts he’s trying to explain.

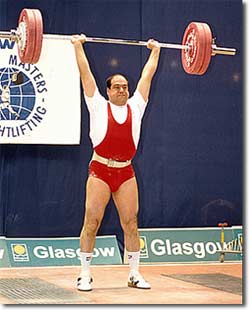

Completing a clean and jerk of 135 kg (298 lbs) at the 1999 World

Masters Weightlifting Championships in Glasgow, Scotland

|

Meltzer

began his career in condensed matter physics, and then directed his

research into physics education. But he says he has long been

interested in teaching and learning. Like many physics students, he was

often unsatisfied with the instruction he received. “I was a frustrated

student,” he says, “I felt it could be done better and clearer. After

you learn the material, you feel you could teach it better. I later

learned that it’s not so easy,” he says.

After

receiving his bachelor’s degree in physics from Columbia University in

1974, Meltzer completed a PhD in condensed matter theory at SUNY Stony

Brook in 1985. For several years he conducted research in condensed

matter physics at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the University of

Tennessee, and then at University of Florida. In 1991, he took a

position at Southeastern Louisiana University in Hammond, Louisiana,

where his interests began to shift towards teaching. So after finishing

up some work on condensed matter theory, Meltzer decided to focus his

research on physics education.

In

1998 he moved to Iowa State University, and set up a physics education

research group there. In addition to developing the flashcard system,

Meltzer investigates student understanding of a variety of physics

topics. For instance, Meltzer and his colleagues recently studied some

of the difficulties students have with thermodynamics, and now he’s

working on developing materials to help students better understand

these concepts.

Aside from his

physics and physics education research, Meltzer has studied the

physiology of weight lifting, which also happens to be a hobby of his.

In one study, he investigated the question of how an athlete’s body

weight affects the rate of decline in performance with age. “Do heavier

guys go down quicker? As best as I can tell, my answer was no, the rate

of decline was the same, whether you were light or heavy,” says

Meltzer. This research led to publication in a prestigious sports

science journal. “It’s actually some of my most widely cited work,”

laughs Meltzer.

It’s also been

relevant to him, as he trains for and competes in international masters

Olympic-style weight lifting competitions. He has won medals in several

recent World Masters Championships.

Singing a medley of 43 different national anthems (first couple of

lines only) during the opening ceremony of the 2004 World Masters

Weightlifting Championships, Baden , Austria , September 25, 2004 . The

flag bearers of the teams are marching into the hall, and are visible

on the projection screen in the background.

|

In

addition to competing, Meltzer sings the national anthems at these

events. Meltzer can sing an amazing number of different national

anthems, in the original language. He got started on this unusual hobby

by watching the Olympics as a child. He liked the sports, but he also

really enjoyed the anthems, he says. “I really liked the melodies. They

just seemed to be attractive to me. I liked the sounds and I liked to

sing,” he says.

Meltzer started

learning to sing a few anthems, and he found that for some reason, it

was something he could do well, and he liked doing it. Even better,

people liked to hear him sing. So he decided to learn more and more of

them. Soon the challenge became learning how to pronounce the words,

says Meltzer. “How do you pronounce Mongolian? You can fake it, but it

doesn’t sound good.”

Fortunately, the

physics and academic community has enabled Meltzer to make connections

with people from all over the world who have helped him learn to

pronounce words in some of the most difficult and obscure languages. He

now sings over 130 different anthems, and plans to learn more.

Download complete article in PDF format

|